My Audio Goals

Whenever I start working on a feature of the engine, I’m always confronted with one question: Should I do it from scratch or should I use a third-party library? And, surprisingly, the question is never easy to answer.

Now, I’m not here to talk about my gripes with projects that include thousands (over-exaggerated number) of dependencies. Instead, I’m here to talk about everything audio.

In all honesty, unlike many other features of this game engine, audio is an area that I’m somewhat familiar with. In the past, I was tasked with implementing an audio backend using PortAudio, which is essentially an audio library that abstracts the complex world of native audio APIs. If you thought that the current state of graphics APIs is complicated, then, oh boy, do I have a treat for you.

Either way, at the time, when I finished my implementation of the audio backend, I remember I was so proud of it that I thought I could make it into a separate library and put it on my GitHub. And I did. I called it WonderAudio. And between you and me, it was shit.

It played audio, yes. It even supported 4 audio formats. But it was primitive. The implementation was chaotic and lacked any possibility of expansion. Understand, I created this audio playback library when I was still a programming infant. I barely knew what a sample was, let alone how the sound card works. Besides that, the library did not support 3D audio spatialization. It only played audio directly to the speakers. I added the “ability”–if you can call it that–of adjusting the volume of the samples, but that’s it. It’s safe to say that WonderAudio lacked a lot of features. Perhaps it could work if I just wanted a simple audio backend that plays “2D” sounds. But that is not my intention here. Okay, but what is my intention?

The Nikola Game Engine (shameless plug) is my magnum opus. At least that’s how I like to think about it. With Nikola, I wanted to implement and experiment with features and systems I never even thought about before. One of those features is, you guessed it, audio. But not just any audio. A fully-fledged 3D audio system with the ability to play sounds in a 3D environment. An audio system that enables sounds to have a position, velocity, and direction. Perhaps add some interesting effects like the Doppler Effect. I don’t want to go crazy with it, though. 3D spatialization is where I draw the line. There are certainly other features I could add, but since my intention is mainly to implement an audio system for games, I did not care much for anything else.

To use some very smart audio terminology I stole right from the Game Engine Architecture book, I wanted to “render” a 3D sound. I know it sounds (haha) weird to say “rendering” a 3D sound, but that’s the terminology. In my head, “playing” an audio sample is just sending the samples to the sound card and letting it do its business, without any interference from you. However, “rendering” a sound implies that the samples go through a pipeline that alters the samples in one way or another. Positioning an audio source in a 3D enviornment relative to an audio listener (we’ll get to that, believe me), applying audio effects like the Doppler effect, and even simple things like changing the pitch or volume of an audio source are all related to this idea of “rendering” an audio source.

And so, essentially, I wanted the Nikola Game Engine to have the ability to “render” sound. No compromises.

Furthermore, while Nikola will support audio formats like MP3, OGG, and whatnot, it will not use them directly. I haven’t gotten around to explaining the way resources work in Nikola yet, but, as an overview, resources in this engine are encoded into a custom binary file called nbr that only the engine understands. To convert any audio format into this nbr binary format, resources will first have to go through the NBRTool. The reasons for this approach are discussed thoroughly in the first devlog I made here. But as a summary, this is done to speed up the start-up time of the game engine (since the engine will not spend a long time decoding audio formats) and to disassociate any resource format from the game engine. Again, go read the devlog if you’re interested.

So my requirements are somewhat rough, you can say. I need to “render” 3D audio and I want the audio API to not rely on decoders like MP3 or WAV files. Something like OpenGL for audio would suit my needs. It can handle all of the maths and complexities of 3D audio, while just requiring to be given an array of samples. Huh. I wonder if there’s something like that?

The Thousand Different Ways

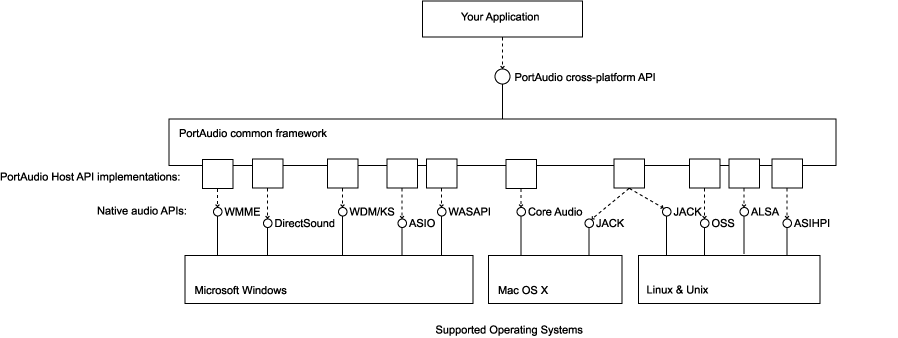

Remember when I told you that the world of audio APIs is actually way more complex and way more annoying than graphics APIs? Well, if you don’t believe me, here’s a cool diagram I got from PortAudio’s website showing which operating systems use which API.

Yeah.

It is definitely possible to make an audio API like PortAudio on your own. But at what cost? Less dependencies, yes. But a waste of time. Unless you are very interested in this sort of thing, I don’t see a reason to do it all from scratch. This is coming from the dude who’s making a game engine from scratch, but still. That’s why I knew from the very beginning that if I had to have a good audio system, I had to use a third-party library. But which third-party library will I use? What a great question, viewer. Reader. Seer?

In my view, there are two kinds of audio APIs: the “backend” APIs and the “frontend” APIs.

The backend APIs are a very thin layer on top of the native APIs that the operating system supports. They usually have an “audio callback” that you can supply, which will be called in a background thread anytime there are new samples to read from or write to. Here’s a simple example from the WonderAudio library I was talking about earlier.

int AudioSource::Callback(const void* inputBuffer,

void* outputBuffer,

unsigned long frameCount,

const PaStreamCallbackTimeInfo* timeInfo,

PaStreamCallbackFlags flags,

void* userData)

{

float* output = (float*)outputBuffer;

AudioSource* src = (AudioSource*)userData;

unsigned long framesRead;

framesRead = src->m_Data->Read(frameCount, output);

for(int i = 0; i < frameCount; i++)

{

*output++ *= src->m_Volume;

// This line is only for stereo audio, not for mono

if(src->m_StreamParam.channelCount > 1)

*output++ *= src->m_Volume;

}

// The clip is completed if no more frames can be read

if(framesRead < frameCount)

return paComplete;

return paContinue;

}

I won’t focus on the details here because this is not what I’m here to talk about, but you can see that these backend APIs are quite “hands off” when it comes to handling audio. They still do a lot, but just not enough.

Besides PortAudio, there’s also MiniAudio, which is essentially the same as PortAudio except it also includes a higher-level “frontend” API you can use. This frontend API includes all of the features I wanted for my audio system. 3D spatialization, support for the Doppler effect, and more. On top of that, MiniAudio is a single-header library. My absolute favorite. However, I did not choose it.

If you remember from before, I did say that the Nikola Game Engine uses a custom resource binary for saving audio data rather than the more “traditional” formats like MP3, WAV, OGG, and what have you. While MiniAudio does allow you to use custom decoders and encoders to read and write your PCM data, it is very annoying and complicated to work with. The frontend side of MiniAudio was clearly made to be used with the ma_sound data structure, which is the all-encompassing audio source type for playing sounds. Again, we can make ma_sound use our own custom decoders, but it is an annoyance more than it is helpful.

What I needed was an API that had the same features as the frontend of MiniAudio had, but without the reliance on traditional decoders. A way to send data to the audio pipeline without any presumptions of where the data came from. And so, this is where our new friend OpenAL comes into “play”. There was a very advanced joke there, but you probably missed it. Doesn’t matter. Let’s move on.

An Introduction To OpenAL

OpenAL is the perfect API for my needs. It handles 3D sound spatialization and even has support for the Doppler effect. It doesn’t care about your data at all. It just requests the PCM samples and goes along. It is not the best audio API, however. Like with everything, OpenAL has its pros and cons. For example, OpenAL does not support floating-point samples natively. Rather, it’s an extension. I’m guessing they did this since not every sound card out there supports floating-point samples. But it’s a minor inconvenience in the grand scheme of things.

Now, OpenAL was created back in the early 2000s by the folks at Loki Software. The same folks who vigorously supported the development of SDL. It was created back when OpenGL was very popular and “loved”. The design of OpenAL’s API is heavily inspired by OpenGL. OpenAL was actually very easy for me to learn since I was familiar with OpenGL already. However, much like OpenGL, OpenAL doesn’t have one implementation. While OpenAL was created by Loki Software (a great name, by the way), it is largely developed currently by Creative Labs. If I’m not mistaken (and I could be), the version Creative Labs is currently developing is proprietary. However, there is an open source implementation of OpenAL called OpenAL-Soft, and this is the one that I’ve been using.

Again, the API design or specification is still the same, it’s just that the implementation is different. Very obvious. Not complex at all. Either way, let’s take a deeper look into the API, shall we?

OpenAL Device And Contexts

Now, in order to start working with OpenAL in the first place, we have to “open” an ALCdevice. Essentially, think of this as a gateway into the sound card. Once the audio device is opened, we can start doing our magic. Opening an audio device in OpenAL is actually quite easy, and this will be a trend with OpenAL moving forward.

ALCdevice* al_device = alcOpenDevice(nullptr);

The alcOpenDevice function takes in a string that identifies a specific audio device you might like to open. You can enumerate through the various devices on your system using the alcGetString function, passing in the ALC_DEVICE_SPECIFIER property to know how many devices your system has and what they are exactly. However, we can just pass a nullptr to let OpenAL choose the default audio device for us. And, for 90% of the time, that’s the best option.

Since alcOpenDevice returns a pointer, we can easily check for its validity.

NIKOLA_ASSERT(al_device, "Failed to open an OpenAL device");

Keep in mind that there can only be one OpenAL device at a time. We cannot open more than one device. I haven’t tried it myself, but I’m pretty sure your system will explode or something like that. So don’t.

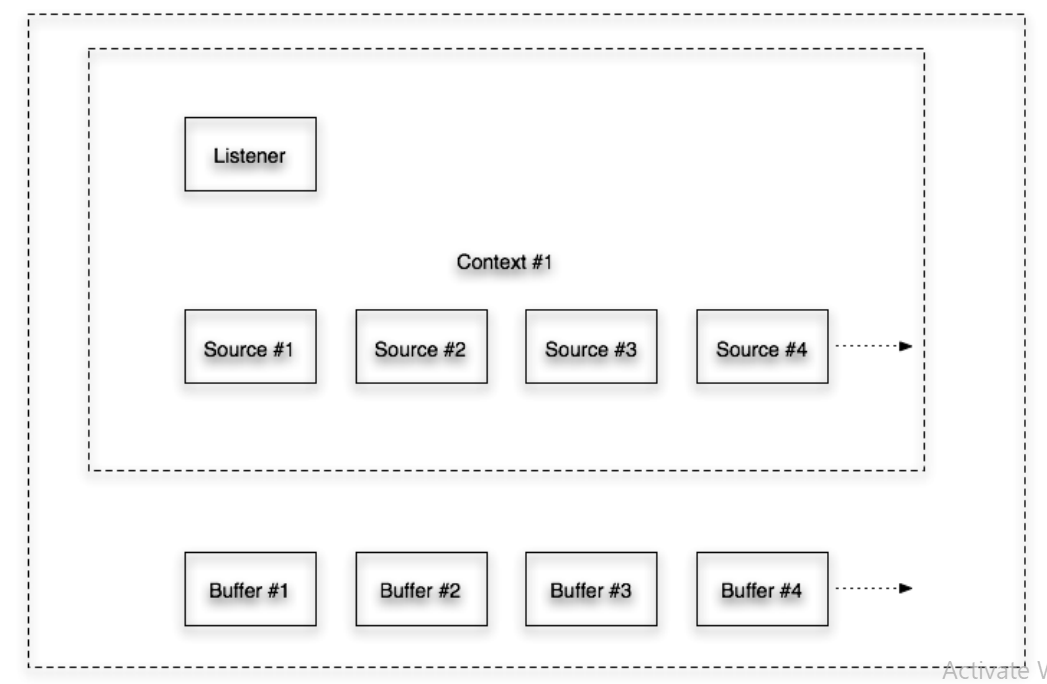

Besides the audio device, there’s also an OpenAL context we have to initialize. To my knowledge, contexts manage all the resources that get created throughout the application. We can switch the contexts using the alMakeContextCurrent and passing in the context we wish to activate or a nullptr to not set any contexts at all.

Basically, an OpenAL device can have multiple contexts, and contexts can have multiple buffers and audio sources. However, for our purposes at least, one OpenAL context is sufficient. And we can create a context like such:

ALCcontext* al_context = alcCreateContext(al_device, nullptr);

alcMakeContextCurrent(al_context);

The second parameter of the alcCreateContext function actually accepts an array of “attributes”. Attributes are basically certain settings the context can have. But that’s out of the scope of this article. You can check out their documentation if you are interested, though.

Either way, besides the audio device and context, OpenAL also has three defining types that we will be using throughout this article: alBuffer, alSource, and alListener.

OpenAL Buffers

The alBuffer, as the name implies, is where the data lives. It’s a buffer of memory that can be given to alSource later on. We can have multiple buffers, each with varying sizes and information. One of the most important functions with this type is the alBufferData. Below, I’ve added a simple example of how an alBuffer can be created. And, as you’ll come to see, it is very similar to the way OpenGL handles its resources.

u32 buffer_id;

alGenBuffers(1, &buffer_id);

alBufferData(buffer_id, AL_FORMAT_MONO8, samples, sizeof(samples), 48000);

And no, this is not OpenGL code. This is OpenAL code.

The alBufferData function takes the buffer ID, the format of the buffer, the actual sample data, the size in bytes of the sample data, and the sample rate. Now, OpenAL expects the data to be in PCM format and not just the raw samples. And there is a distinction between them. I just don’t know exactly what it is. Go look it up if you’re interested.

OpenAL supports 4 (technically it supports more with the extensions) PCM sample formats, which I converted into 3 types in my engine.

enum AudioBufferFormat {

/// Indicates an audio buffer with 8-bit unsigned integers per sample.

AUDIO_BUFFER_FORMAT_U8 = 20 << 0,

/// Indicates an audio buffer with 16-bit signed integers per sample.

AUDIO_BUFFER_FORMAT_I16 = 20 << 1,

/// Indicates an audio buffer with 32-bit floats per sample.

///

/// @NOTE: This might not be supported on every platform.

AUDIO_BUFFER_FORMAT_F32 = 20 << 2,

};

OpenAL’s formats are these:

enum OpenALFormat {

AL_FORMAT_MONO8,

AL_FORMAT_MONO16,

AL_FORMAT_STEREO8,

AL_FORMAT_STEREO16,

};

Again, if we have the extensions enabled, we can use even more types. But let’s just focus on these for now.

Now, if you don’t know audio terminology, let me bestow upon you a bit of unsure enlightenment. Any audio buffer that has only one channel is considered “Mono,” which comes from the Greek “monos,” which means alone. I used Google. On the other hand, “Stereo” is for any audio buffer with two channels. I don’t know the etymology of that one, and I’m too lazy to look it up. Now there are systems and audio setups with up to 7 channels. It’s usually those surround audio systems you’d see being used by rich people. And while OpenAL does have support for more than 2 audio channels, they are, much like floating point formats, very dependent on your current system and are therefore just extensions in OpenAL.

Nonetheless, once we’ve filled a buffer with some data, we can supply that buffer to an alSource.

OpenAL Sources

Generating and using an audio source is very much similar to generating and using an audio buffer.

u32 source_id;

alGenSources(1, &source_id);

alSourcei(source_id, AL_BUFFER, buffer_id);

We use the alSourcei function here to set the AL_BUFFER property of the audio source to the buffer_id. But we can also queue buffers or chain them together to be played one after the other using the alSourceQueueBuffers function.

alSourceQueueBuffers(source_id, buffers_count, &buffers[0]);

It just expects the source ID, how many buffers to queue, and an array of buffer IDs. To my knowledge, there is no maximum number of buffers the audio source can queue, but, for convenience’s sake, I put a limit of 32 on the number of buffers that can be queued.

Besides setting the buffer property, we can set other properties of the audio source as well. This is where we set things like the volume (which his called “gain” in OpenAL), the pitch, the position, the velocity, and all that jazz.

alSourcef(source_id, AL_GAIN, volume);

alSourcef(source_id, AL_PITCH, pitch);

alSourcefv(source_id, AL_POSITION, &position[0]);

alSourcefv(source_id, AL_VELOCITY, &velocity[0]);

alSourcefv(source_id, AL_DIRECTION, &direction[0]);

alSourcei(source_id, AL_LOOPING, is_looping);

There are also audio source “commands” we can use. Commands like play, stop, pause, and rewind.

alSourcePlay(source_id);

alSourceStop(source_id);

alSourcePause(source_id);

alSourceRewind(source_id);

We can also query for certain states of the audio source to see if it’s currently playing a buffer, for example.

i32 state;

alGetSourcei(source_id, AL_SOURCE_STATE, &state);

if(state == AL_PLAYING) {

// Do something here...

}

In order to have 3D audio spatialization, however, the audio buffer must have only 1 channel. It cannot be anything other than a Mono, basically. I don’t know if this is a limitation of OpenAL or a limitation of 3D audio in general, but it makes it annoying to use any sound since I have to make sure it contains only one channel. Usually, that means I have to run the sound file through a sketchy online converter. I can, perhaps, have a system that converts stereo buffers into mono buffers, but that’s a problem for another day.

Still, enabling 3D spatialization doesn’t only require the audio buffer to be mono. It also requires the audio scene to have an “audio listener”.

OpenAL Listeners

You see, when we’re playing “2D” audio, we don’t really have a concept of a source and a listener. It’s just an array of samples being fed to the sound card and played out of our speakers. And while that process still occurs when we play 3D audio, the logic is different on our own end.

Since the audio source lives in a 3D world, it needs to be heard by someone. A listener, let’s just say. If this listener is near the audio source, the sound is heard. As the listener moves away from the audio source, a feature known as audio attenuation starts to take place. Audio attenuation is the gradual falloff of the audio source as the listener backs away. The volume of the audio source slowly decreases until it’s all but gone. Likewise, the opposite is true. As the listener gets closer to the audio source, the volume (or “gain”) slowly starts to increase. This is the crux of 3D audio spatialization, if you will. Audio attenuation is what gives us the “illusion” of 3D audio in games.

Now, unlike audio buffers and audio sources, we cannot have more than one audio listener. By default, there is an audio listener OpenAL provides to you. The position and velocity of this audio listener are all zeroed out, of course. You can come in and change it as you like. But you cannot have any other audio listeners besides this “global” listener. And, if you think about it, it makes sense. Even in multiplayer games, there is only one audio listener at a time, and that’s usually the player. Perhaps the audio listener follows the camera around constantly. But, nonetheless, it’s almost always a single audio listener.

And, much like the two other sections, audio listeners in OpenAL are very easy to use. Since the audio listener is already “generated” for us by OpenAL, all we can do is set its properties as such:

alListenerf(AL_GAIN, volume);

alListenerfv(AL_POSITION, &position[0]);

alListenerfv(AL_VELOCITY, &velocity[0]);

I did forget to mention that OpenAL’s coordinate system is the same as OpenGL’s. A right-handed coordinate system. The negative Z-axis is usually where the player is looking towards. If you’re using a left-handed coordinate system, you can simply negate the Z-axis. At least that’s what they say in the documentation;

Conclusion

Now, listen, it will not be a surprising claim to say that the way I handle audio stuff is probably not the best way ever. I’m not claiming it either. This audio system is still an infant. A baby who has not yet grown up. I implemented this audio system in a week or so. Nothing great was created in a week. However, I am happy with the current state of the audio system. It does what I want it to do without any errors. A step in the right direction, I say.

Later on, I might come back and expand upon it a bit more. But, for now, I’m ready to move on to other ventures and experiment with other systems.

Feel free to use any code you saw in this article, or you can check out the full implementation over on GitHub.